Every time you shop online, scroll through social media, or check your bank balance, you’re experiencing digital nudging. These subtle design choices in apps and websites influence how we behave, sometimes for our benefit, and sometimes purely to serve a company’s bottom line.

Some nudges are positive, like a savings app that helps you put money aside without even noticing. Others are manipulative, like dark patterns in e-commerce that pressure you into spending more than you intended.

The real question is: when is behavioural design in apps helping us, and when is it tricking us?

Not all nudges are harmful. Many fintech nudges are designed to improve our financial wellbeing and reduce procrastination.

These are nudges that support healthy behaviours, whether in money, investing, or personal growth. They show how behavioural economics in apps can be used to help us, not just exploit us.

Small changes can make a big difference.

Unfortunately, digital nudging doesn’t always work in our favour. Many platforms rely on dark patterns online to keep us spending, scrolling, or sharing data.

Technology is a useful servant, but a dangerous master.

This is behavioural design in technology at its worst, steering us towards choices that benefit companies, not consumers.

Unfortunately, digital nudging doesn’t always work in our favour. Many platforms rely on dark patterns online to keep us spending, scrolling, or sharing data.

This is behavioural design in technology at its worst, steering us towards choices that benefit companies, not consumers.

Not every example of nudging in technology is black or white. Some design choices sit in a grey zone.

For example:

The ethical challenge lies in whether these nudges are transparent, reversible, and truly in the user’s interest. Increasingly, behavioural scientists argue for boosting, empowering people with decision-making skills and autonomy, instead of silently steering them. Boosts build long-term competence, while nudges simply adjust the environment.

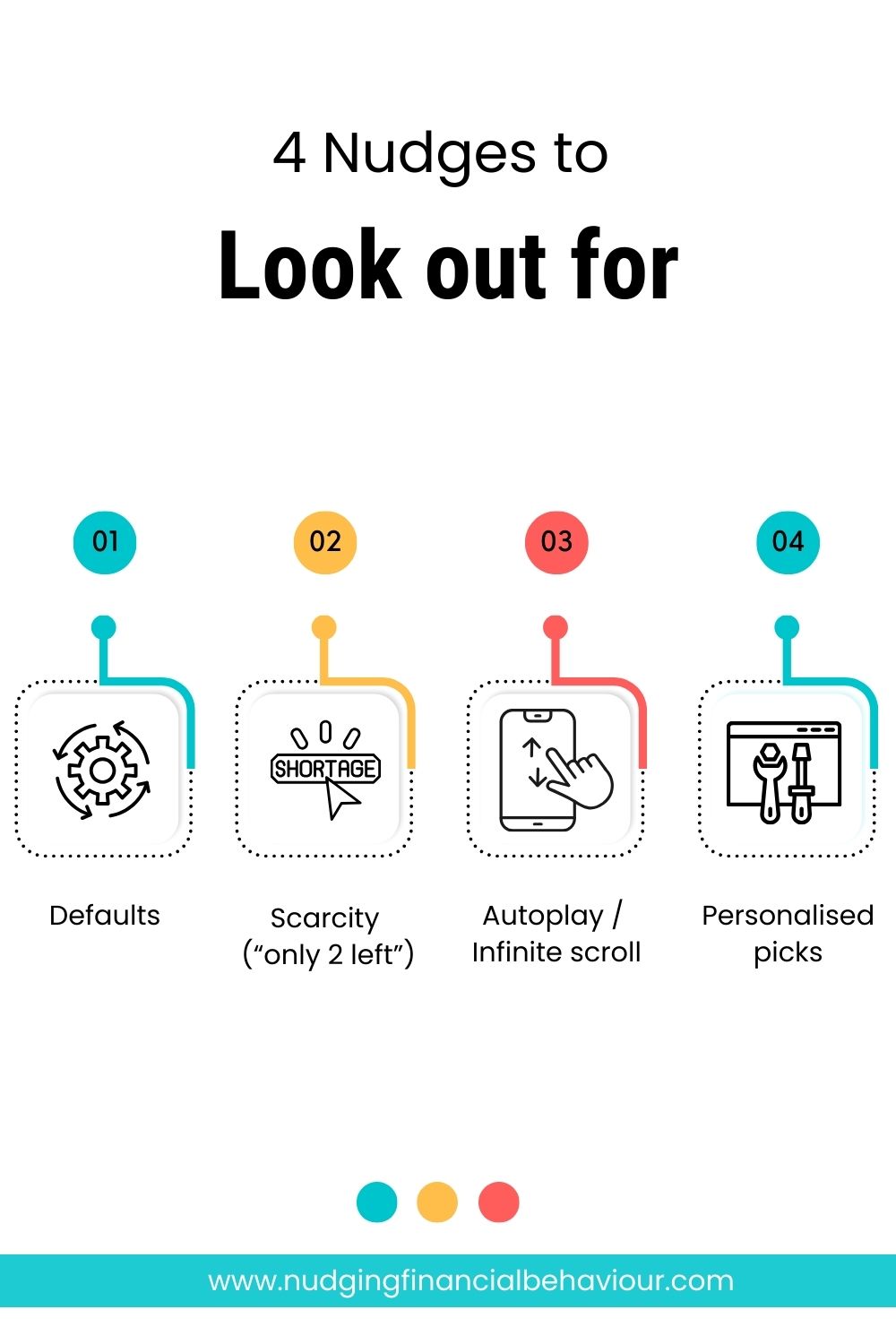

The good news: once you can spot digital nudges, you can resist the manipulative ones and embrace the helpful ones. Here’s how:

1. Watch out for urgency cues. Countdown clocks and “only X left” messages are often just psychological tricks.

2. Double-check defaults. Don’t assume pre-ticked boxes are right for you; they usually aren’t.

3. Set up your own nudges. Turn off autoplay in streaming apps, use budgeting apps that send positive reminders, and schedule alerts to review your subscriptions.

4. Choose ethical apps. Some fintech tools make a point of transparent design, allowing you to customise or opt out easily.

These steps help you stay in control, turning the tables on behavioural design in apps.

Digital nudging is the invisible hand shaping your daily choices. Some nudges are empowering, helping you save money, invest smarter, or stick to a healthy routine. Others are manipulative, exploiting behavioural biases to drain your wallet and attention.

The difference comes down to awareness. Once you understand how behavioural economics in technology works, you can choose which nudges to accept and which to push back against.

Next time you’re shopping online, scrolling your feed, or watching just “one more” episode, pause and ask yourself: am I making this choice, or is the app making it for me?

The greatest weapon against stress is our ability to choose one thought over another.

Share your answers in the comments below.

Share your answers in the comments below.

I am passionate about helping people understand their behaviour with money and gently nudging them to spend less and save more. I have several academic journal publications on investor behaviour, financial literacy and personal finance, and perfectly understand the biases that influence how we manage our money. This blog is where I break down those ideas and share my thinking. I’ll try to cover relevant topics that my readers bring to my attention. Please read, share, and comment. That’s how we spread knowledge and help both ourselves and others to become in control of our financial situations.

Dr Gizelle Willows

PhD and NRF-rating in Behavioural Finance

[user_registration_form id=”8641″]

“Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” – George E.P. Box

Receive gentle nudges from us: