In this post, you’ll learn why you place extra value on things you already own. And how marketers, retailers, and employers use that behavioral trait to entice you into action (or inaction). From your willingness (or unwillingness) to pay market price, to the value of a chocolate bar that is already in your hand; the endowment effect examples trickle all the way into your investment portfolio.

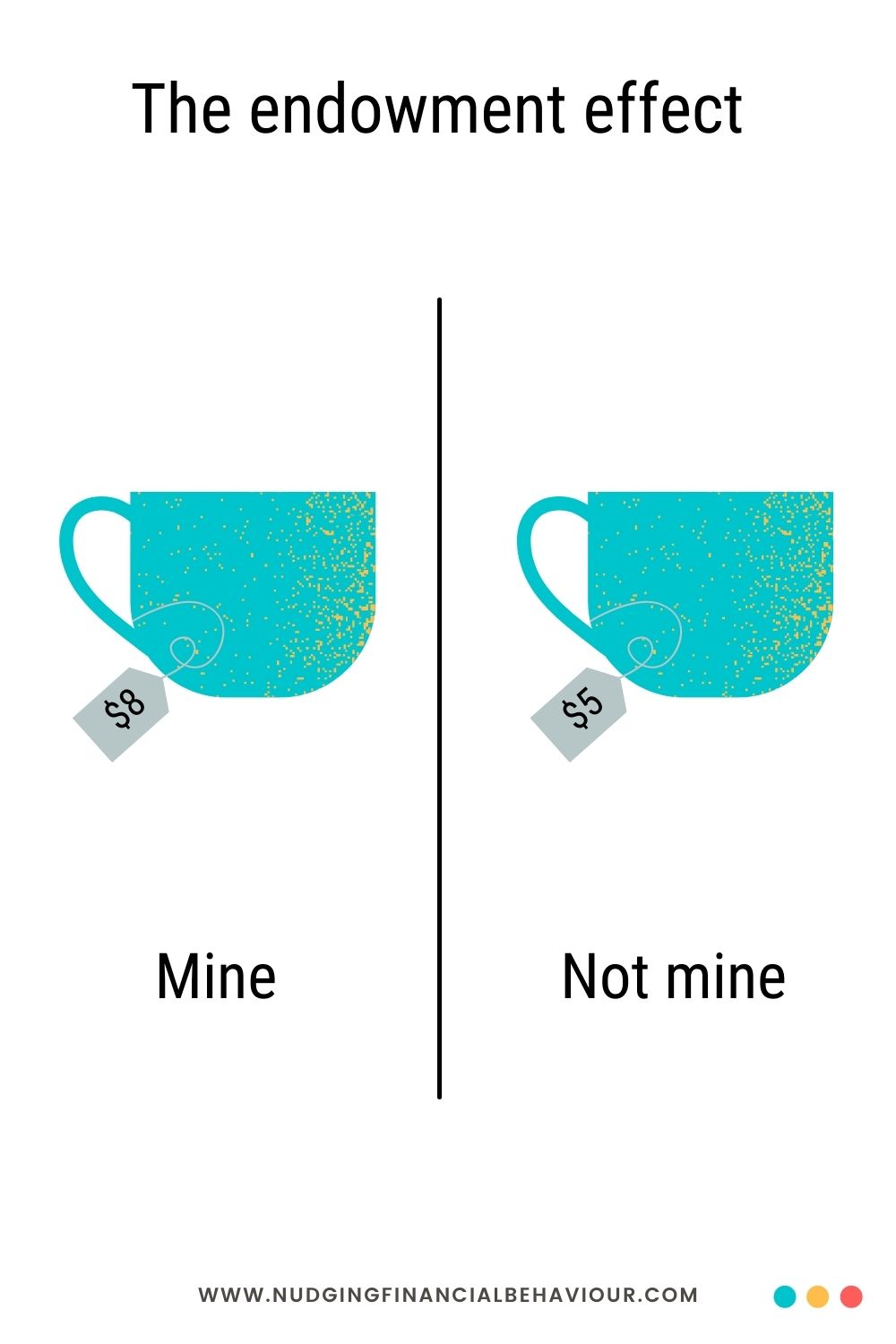

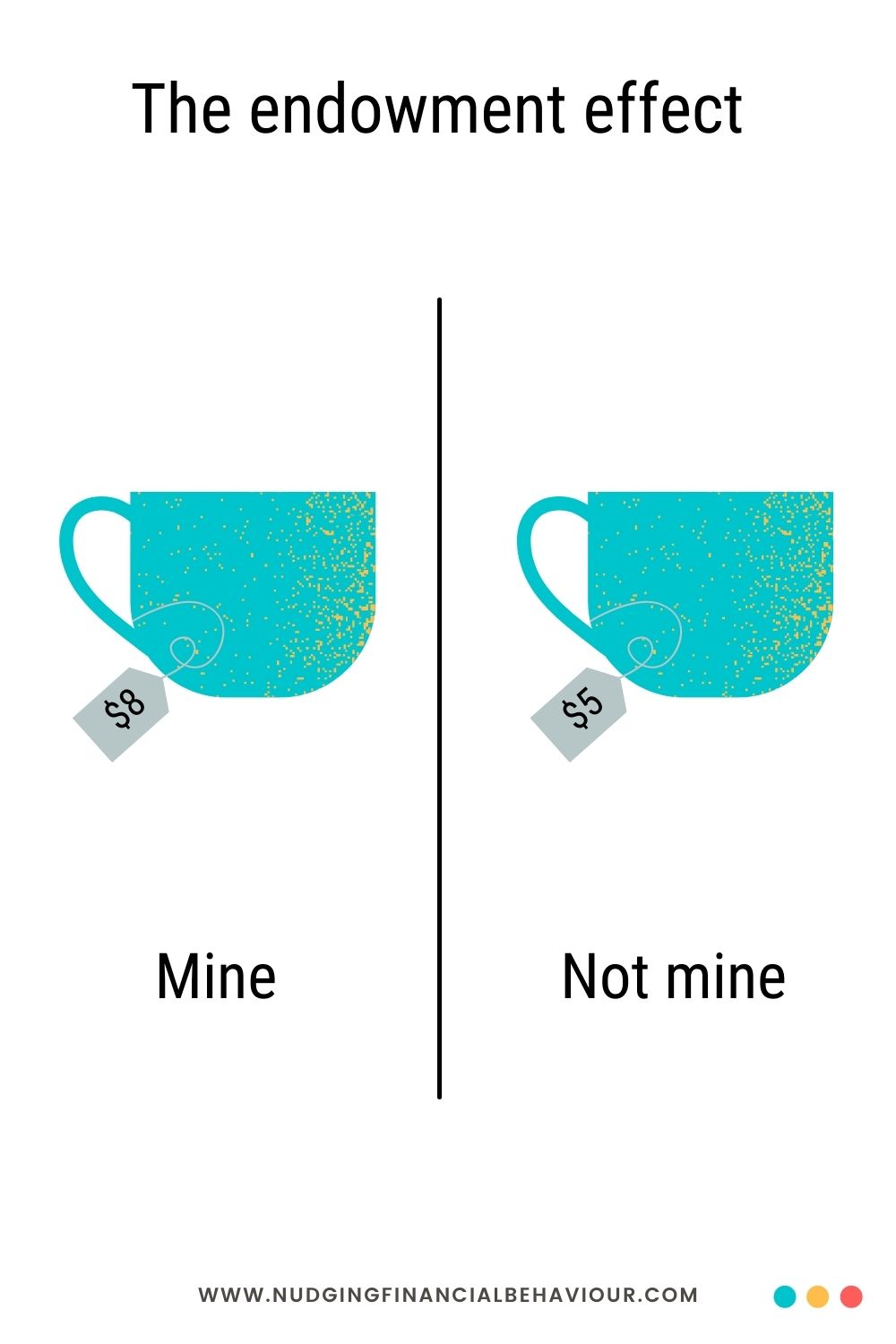

The endowment effect states that you value something more because you own it. This is well-explained by the classic mug experiment

Participants in the study were randomly divided into two groups. In the first group, each participant was given a mug and asked what the minimum price would be for them to be willing to sell that mug. In the second group, the participants were given nothing but were asked what the maximum price would be for them to be willing to pay to buy the mug.

Standard economics would predict that those two prices would be the same. But they weren’t.

The minimum selling price was higher than the maximum buying price. Participants who were given a mug expected a higher price to give up the mug, than the price that other participants were willing to pay to purchase the mug. This shows that people will pay more to retain something they own than to obtain something owned by someone else.

The endowment effect states that you value something more because you own it. This is well-explained by the classic mug experiment

Participants in the study were randomly divided into two groups. In the first group, each participant was given a mug and asked what the minimum price would be for them to be willing to sell that mug. In the second group, the participants were given nothing but were asked what the maximum price would be for them to be willing to pay to buy the mug.

Standard economics would predict that those two prices would be the same. But they weren’t.

The minimum selling price was higher than the maximum buying price. Participants who were given a mug expected a higher price to give up the mug, than the price that other participants were willing to pay to purchase the mug. This shows that people will pay more to retain something they own than to obtain something owned by someone else.

This happened even when there was no cause for attachment to the mug and it was only given to them a few moments before they set their price. What we can learn about this is that once you have something, foregoing it feels like a loss (and we are all loss averse).

This is also why we are better at collecting things than throwing things away.

Now, what might a wise marketer do with this knowledge? Perhaps tell you to try the products out for a bit before paying? How many mobile apps say you’ll get 30 days free use and only billed thereafter? You think, “great, let me use this for 30 days and then I’ll cancel”. But… once you’ve started using it, you build an attachment and cancelling it feels like a loss. Marketers are so clever.

If you’re beginning to understand the motivation for the endowment effect, you’ll probably understand why it’s sometimes referred to as the IKEA effect. What happens when you visit IKEA? You like the design of a piece of furniture. You purchase a box of parts and directions on how to piece them together. You’re “building” your own desk. What happens next is that you place a higher value on it than anyone else would (even if the desk isn’t perfectly level). That’s the IKEA effect.

So, possession of an item is one thing. Now we add the fact that you are actually building it yourself! Explains why owner-built properties in the real estate market tend to be overpriced…

If you’re beginning to understand the motivation for the endowment effect, you’ll probably understand why it’s sometimes referred to as the IKEA effect. What happens when you visit IKEA? You like the design of a piece of furniture. You purchase a box of parts and directions on how to piece them together. You’re “building” your own desk. What happens next is that you place a higher value on it than anyone else would (even if the desk isn’t perfectly level). That’s the IKEA effect.

So, possession of an item is one thing. Now we add the fact that you are actually building it yourself! Explains why owner-built properties in the real estate market tend to be overpriced…

Another example of how the endowment effect is used is with staff incentive schemes. This was tested on a group of teachers.

All teachers were incentivised to meet certain performance targets. However, the payout of the bonuses was done differently for different groups.

In one group, teachers received the bonus at the end of the year (if they met the targets). In another group, teachers received 50% of the bonus at the beginning of the year and the other 50% at the end of the year. However, if they didn’t meet the targets, they needed to pay back the 50% that they got at the start of the year.

Any guesses as to which group performed better?

By a significant margin, the group of teachers that would have to pay back part of the bonus outperformed the other group. They were up against the feeling of losing the 50% bonus they had already received.

This is a textbook example of how share options and retention schemes work. Pay you at the start of the term. That way, they can almost be assured you won’t leave until that term comes to an end.

Another example of how the endowment effect is used is with staff incentive schemes. This was tested on a group of teachers.

All teachers were incentivised to meet certain performance targets. However, the payout of the bonuses was done differently for different groups.

In one group, teachers received the bonus at the end of the year (if they met the targets). In another group, teachers received 50% of the bonus at the beginning of the year and the other 50% at the end of the year. However, if they didn’t meet the targets, they needed to pay back the 50% that they got at the start of the year.

Any guesses as to which group performed better?

By a significant margin, the group of teachers that would have to pay back part of the bonus outperformed the other group. They were up against the feeling of losing the 50% bonus they had already received.

This is a textbook example of how share options and retention schemes work. Pay you at the start of the term. That way, they can almost be assured you won’t leave until that term comes to an end.

Similar to how I said, “marketers are so clever”, I’m tempted to say “HR is clever”, but I can do better than that: “You are clever”. But there’s one proviso… you’ve got to have self-control.

Because you know you’re psychologically wired to value something once you own it, why not turn this on its head? Any payouts you receive that still have clauses attached to them (retention payments, performance payouts, etc.) – invest the money!

This might sound bizarre, as we all want to spend payouts, but consider for a moment that you haven’t technically earned that money yet.

You haven’t worked the x number of days or met the target. If you invest these payouts rather than spend them, it also gives you the freedom to change your mind if you decide you want to move companies. And that then removes the anxiety of losing something.

By definition, a bonus is a “reward”, usually for good performance. Why not make the bonus payment feel like that? Too often we ‘bank’ on that bonus and spend it before we receive it. There’s a risk here, in that you can’t always be certain you’ll receive a bonus. But even if you do, imagine the joy of receiving a payout and then rewarding yourself, rather than paying off something you couldn’t wait for? Just an idea…

Similar to how I said, “marketers are so clever”, I’m tempted to say “HR is clever”, but I can do better than that: “You are clever”. But there’s one proviso… you’ve got to have self-control.

Because you know you’re psychologically wired to value something once you own it, why not turn this on its head? Any payouts you receive that still have clauses attached to them (retention payments, performance payouts, etc.) – invest the money!

This might sound bizarre, as we all want to spend payouts, but consider for a moment that you haven’t technically earned that money yet.

You haven’t worked the x number of days or met the target. If you invest these payouts rather than spend them, it also gives you the freedom to change your mind if you decide you want to move companies. And that then removes the anxiety of losing something.

By definition, a bonus is a “reward”, usually for good performance. Why not make the bonus payment feel like that? Too often we ‘bank’ on that bonus and spend it before we receive it. There’s a risk here, in that you can’t always be certain you’ll receive a bonus. But even if you do, imagine the joy of receiving a payout and then rewarding yourself, rather than paying off something you couldn’t wait for? Just an idea…

If we over value things – merely because we own them (the mere ownership effect) – that implies that we will overvalue our investments. In turn, making it difficult for us to sell them at market value.

Adding the IKEA effect to this, imagine the impact of building your own portfolio? All the time and effort you put into researching different shares and investment vehicles. Doesn’t matter how dodgy the result, you’re attached.

Also, research tells us that the more effort you put into something, the more you value the outcome (a behaviour known as effort justification). So, if you’re inclined to do lots of research before buying something, you get hit with the endowment effect and effort justification (doubly screwed).

Your efforts aren’t unjustified. Our susceptibility to confirmation bias implies that we need to do a bit of research before executing a purchase decision. But what you need to be careful of is how you then perceive that investment after you’ve bought it. Stay open-minded.

If we over value things – merely because we own them (the mere ownership effect) – that implies that we will overvalue our investments. In turn, making it difficult for us to sell them at market value.

Adding the IKEA effect to this, imagine the impact of building your own portfolio? All the time and effort you put into researching different shares and investment vehicles. Doesn’t matter how dodgy the result, you’re attached.

Also, research tells us that the more effort you put into something, the more you value the outcome (a behaviour known as effort justification). So, if you’re inclined to do lots of research before buying something, you get hit with the endowment effect and effort justification (doubly screwed).

Your efforts aren’t unjustified. Our susceptibility to confirmation bias implies that we need to do a bit of research before executing a purchase decision. But what you need to be careful of is how you then perceive that investment after you’ve bought it. Stay open-minded.

At the very least, be mindful of the endowment effect. It’s great that we can buy something and try it out with the option of returning for a full refund if we’re not happy. But don’t entertain this type of consumer behaviour. Beware behavioral economics. You now KNOW that you’re less likely to give things up once you have them in your possession.

Be mindful of overvaluing your investments simply because of the vast amount of effort you put into analysing them. Don’t miss future changes because you’re happy with your historical research efforts. Always acknowledge evidence that tries to disprove a decision.

The IKEA effect: When you build something yourself you value it way more than you should.

Building an IKEA desk is fine but equating its value to that of a craftsman is beyond biased. It’s the same senseless comparison when you try compare your IKEA investment portfolio to that of one put together by a professional.

Let us know in the comments below.

Let us know in the comments below.

I am passionate about helping people understand their behaviour with money and gently nudging them to spend less and save more. I have several academic journal publications on investor behaviour, financial literacy and personal finance, and perfectly understand the biases that influence how we manage our money. This blog is where I break down those ideas and share my thinking. I’ll try to cover relevant topics that my readers bring to my attention. Please read, share, and comment. That’s how we spread knowledge and help both ourselves and others to become in control of our financial situations.

Dr Gizelle Willows

PhD and NRF-rating in Behavioural Finance

Receive gentle nudges from us:

[user_registration_form id=”8641″]

“Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” – George E.P. Box